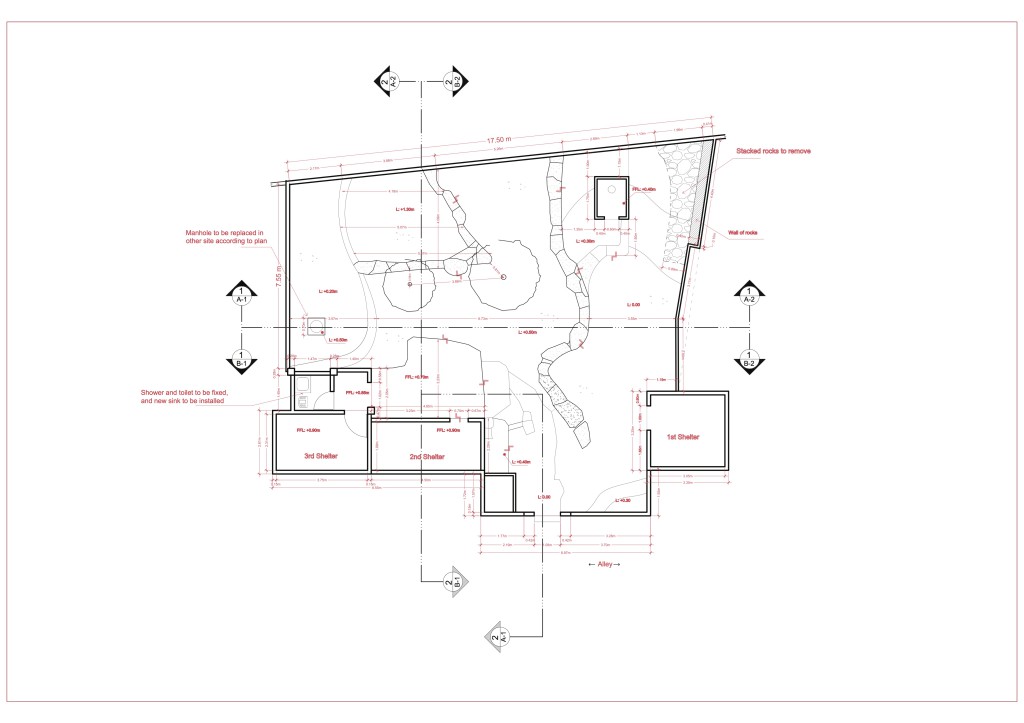

The three shelters site consisted of three original 1950s UNRWA-built structures (three rooms, one latrine and a water reservoir) that were still standing. This small plot contains several historical periods in the development of the camp: rocks and olive trees (the site as known by refugees when they first arrived in 1949), the shelters built by UNRWA to replace the worn tents, the public toilet, and new buildings. In addition to the “historical relevance”, this site contains the material evidence of a particular communal life that exists in the camp.

In December 2013 after surveying the project site, a collaborative design process unfolded among the residents, Campus in Camps participants and DAAR.

Considering the historical value of the architectural elements present at the site anchored to the collective memory of the residents, a non-intrusive but decisive approach was selected to bring new uses to the space and to the camp.

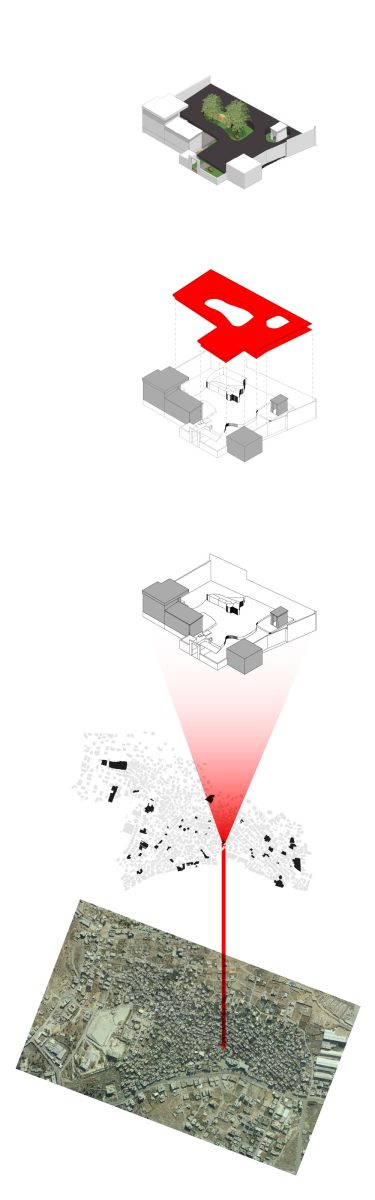

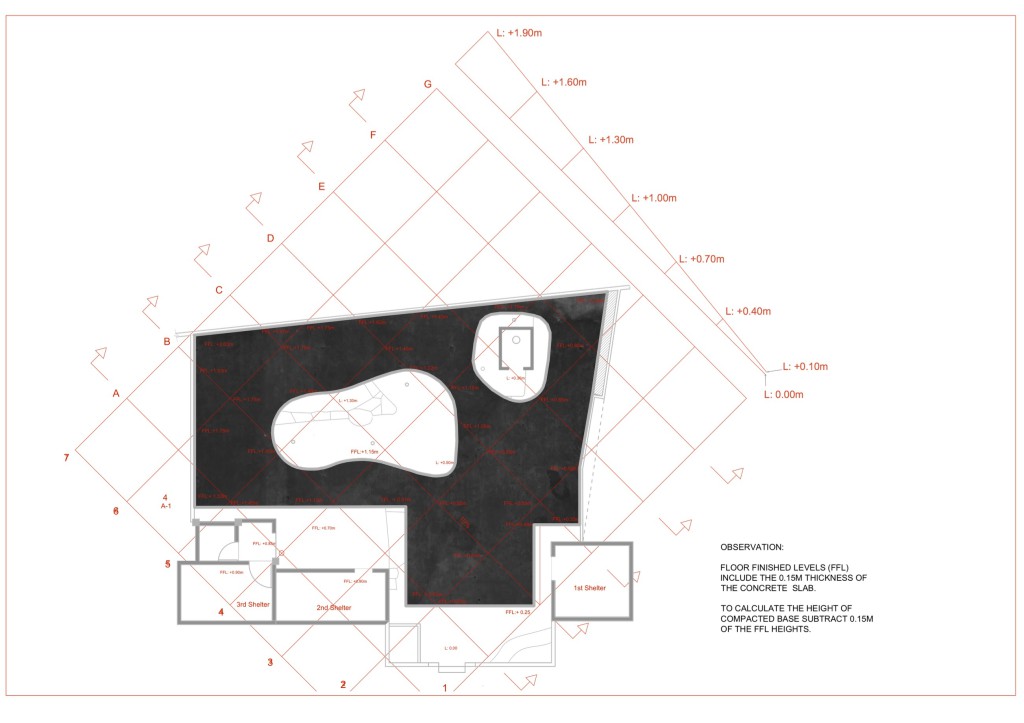

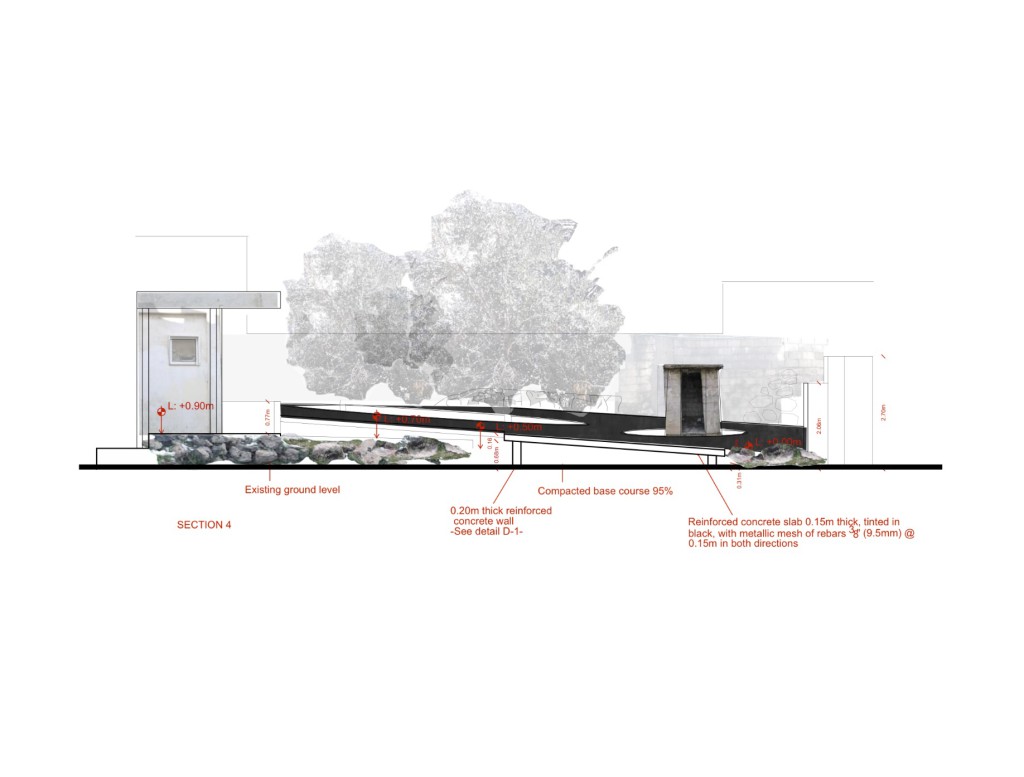

The project was envisioned as a black fifteen centimetre-thick reinforced concrete platform, a sort of theatre stage for events and a neutral frame for the objects present on-site. Similar to temporary structures built for circulation in an archeological site, the black concrete platform was meant to leave the existing shelters as well as the communal latrine, water reservoir and the olive trees intact as a sign of respect for the past in this new beginning.

The platform, built in a way that would appear as “suspended” and “floating” is meant to give the visitors and users the feeling of instability, emphasized by a slight inclination of the platform. The design navigated the tension between the permanency and temporariness of materials and expressed it by architectural form.

The participants of Campus in Camps spent several weeks in dialogue with the neighbour and “owners” of this site and finally an agreement was signed between the popular committee and the family owner of the space to build the project and host activities for all the camp community.

Construction plans began with the excavation for the foundation of the project but after ten days the construction was stopped as the family had now decided to sell the land. The family, the popular committee, and leaders of the camp spent several weeks trying to find a solution. They even offered him another plot but finally the negotiation collapsed after he decided to demolish the shelters.

The plot was left abandoned for months. After, a skeleton for a new house emerged from the site.

This was an extremely frustrating moment, but it also made it even more evident the complexity around “ownership” and the vulnerability of open spaces in the camp, and furthermore it raised the question of how to create a collective awareness on the importance of preserving the camp and its history.

The whole process offered the community a different understanding of the camps: no longer as places without memory but places full of stories that could be told through their urban fabric.

This discovery brought us to the building of a “Concrete Tent”.