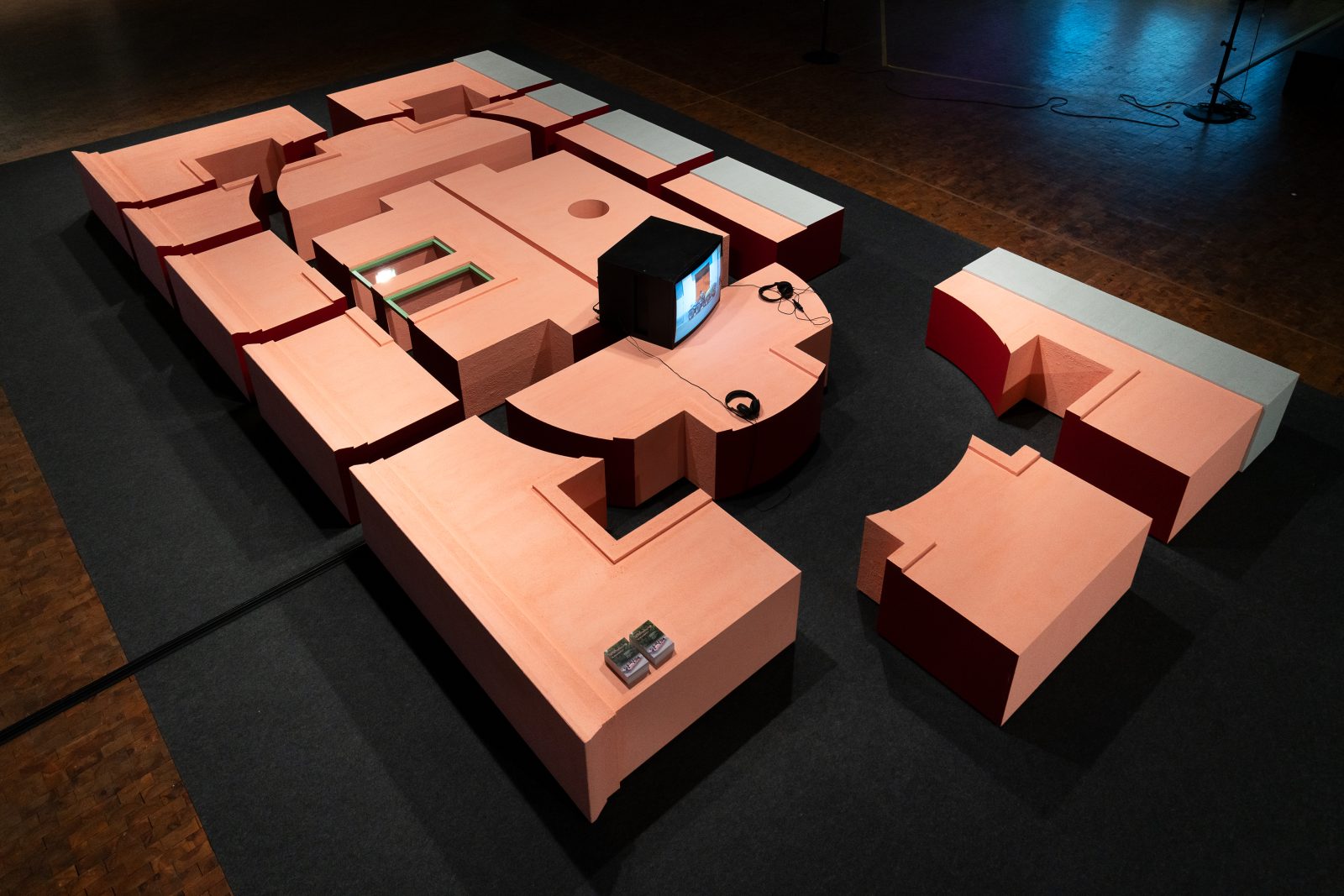

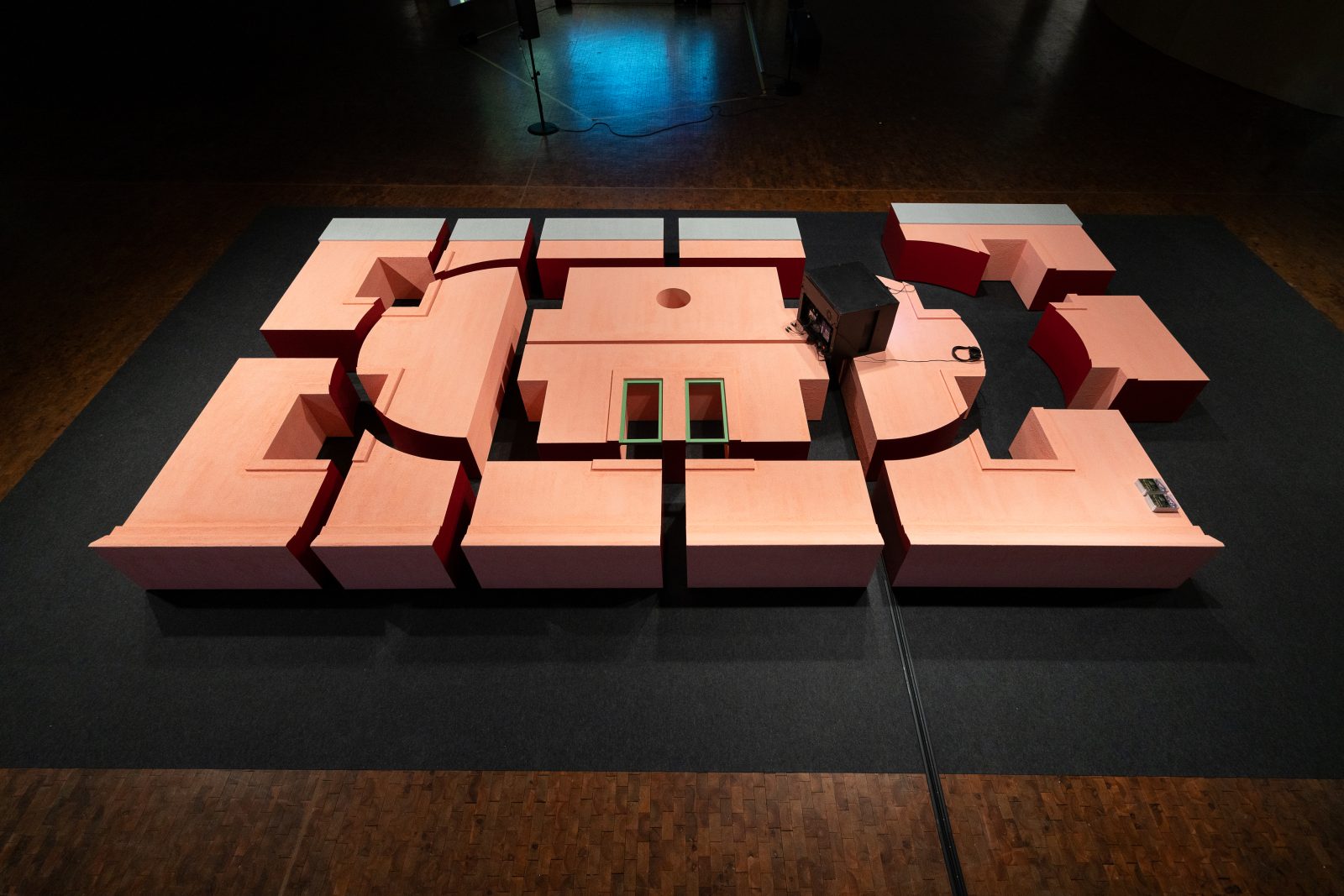

Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza – is the new project by DAAR – Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hilal – which explores the possibility of critical reuse and subversion of fascist colonial architecture through an art installation.

Starting from the decomposition and recomposition of the facade of the Entity of Colonization of the Sicilian Latifundiium (1940) in Borgo Rizza (Siracusa), the installation is composed of several modules-sittings that are the platform of an open discursive space where the public is invited to reconsider critically the social, political and economic effect of fascist and colonial heritage and at the same time is invited to image collectively new common uses. The installation is presented and activated in several venues in Napoli (2022), Berlin (2022), Bruxells (2023) and Albissola Marina (2023).

Video Essay:

01. Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza at the Mostra d´Oltremare in Napoli, May 2022

The first activation of the “Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza” took place in May 2022 at the Mostra d’Oltremare in Napoli, which first opened in 1940. Conceived as a colossal exhibition to display the territories and people overseas in areas colonized by the fascist regime, it closed only 40 days after its opening, when Italy entered the Second World War. It has since had many temporary uses, including hosting refugees from the Second World War and from earthquakes in the 80s; acting as a vaccination center; and providing a venue for public events.

MUSEO MADRE, Napoli

Bellezza e Terrore: luoghi di colonialismo e fascismo

a cura di Kathryn Weir

24.06 — 26.09.2022

02. Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza at the Berlin Biennal, June 2022

The second activation of “Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza” took place at the Akademie der Künste in the Hansa Quarter in Berlin built in 1957 for the International Building Exhibition (Interbau). On this occasion, we were interested in exploring how modernist architecture was deployed for the representation of a democratic Germany. Today, Interbau (1957) and the Karl-Marx-Allee are on the way to becoming UNESCO world heritage sites for their Post-war architectural and urban modernism. With the participation of the public visiting the biennial, members of local associations, and students from New York University Abu Dhabi we looked into what the rhetoric of modernity is hiding, and how it has been mobilized in different contexts. Modernist architectures, both in the former colonies and the colonizing countries, have been built as isolated sacred objects to be admired; therefore, for us, it is not enough just to reuse them, they need to be profaned, to be used against themselves, and open for new common uses different from those they were designed for.

12th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art

The Akademie der Künste in Berlin

June 11- Sep 18, 2022

https://www.berlinbiennale.de/en/

03. Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza at La Loge, February 3 – April 9, 2023

The third activation took place al la loge, a public discussion that revolved around the decolonization of public spaces in Brussels. (2021_URBAN_REPORT_DECOLON_PUBLIC_SPACE_EN_DEF).

04. Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza at 18th International Architecture Exhibition – La Biennale di Venezia, May 20 – November 23, 2023

Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza

A project by DAAR – Sandi Hilal and Alessandro Petti –

Research: Sandi Hilal, Emilio Distretti, Alessandro Petti

Project coordinator: Sara Pellegrini

Public program curator: Matteo Lucchetti

Video Editing: Husam Abusalem

Design assistance and executive production: Orizzontale and Zapoi

Documentation: Pietro Onofri

Website design: NERO editions

Online platform editor: Michele Angiletta for NERO editions

Acknowledgements: Corrado Gugliotta, Salvatore La Rosa, Iole Lianza, Laura Mariano, Remo Minopoli, Nicolò Stabile, Kathryn Weir

Co-commissioned and co-produced by La Loge – Brussels and Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, Madre Museum – Naples, Comune di Albissola Marina

Project supported by the Italian Council (10th Edition 2022) program to promote Italian contemporary art in the world by the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity for the Italian Ministry of Culture.

Artwork

Material: wood, plaster, plexiglass

Dimensions: 350x600x45 cm

Courtesy the artists

Script video essay

TOWARDS AN ENTITY OF DECOLONIZATION

1.

In 1940, the Italian Fascist regime established the “Entity of Colonization of Sicilian Latifundium” following the model of the “Entity of Colonization of Libya” and colonial architecture in Eritrea and Ethiopia.

These territories were considered by the regime “empty,” “underdeveloped,” and “backward” and therefore in need of being “reclaimed,” “modernized,” and “repopulated.”

For this purpose, the “Entity of Colonization” inaugurated eight new rural towns in Sicily, and as many remained unfinished.

Today most of these villages have fallen into ruin.

However, what does not seem to be in ruin is the persistence of fascist, colonial and modernist rhetoric, culture, and politics.

2.

Despite the fall of fascism following the Second World War, Italy’s de-fascistization, unfortunately, remains an unfinished process. This is one of the reasons why there are many visible architectures and monuments, that celebrate the fascist regime.

Moreover, having lost its colonies during the Second World War, Italy has never embarked on a real process of decolonization.

3.

With the re-emergence of fascist ideologies in Europe, it becomes urgent to ask: what kind of heritage is the fascist-colonial and modernist heritage? And, who has the right to re-use it? Should this heritage simply be demolished, or could it be re-oriented towards other ends?

4.

The European colonial/modern project of exploitation, segregation, and dispossession has divided the world into different races and nations, constructing its identity in opposition to “other projects” labeled as traditional or backward. The suppression of alternatives was, and is, an attempt to create a singular modernist/colonial epistemology. Therefore, modernity cannot exist without the disqualification and degradation of other approaches and world views.

5.

In 2017, the nomination of Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its modernist colonial architecture built by the fascist regime during the period of Italian colonization, posed a series of fundamental questions for both the ex-colonized and the ex-colonizers:

Who has the right to preserve, reuse and re-narrate fascist colonial and modernist architecture?

While architectural modernism in particular continues to be celebrated for its progressive social and political agenda, what the modernist rhetoric of progress and innovation obscures is its dark side, namely its inherent homogenizing, authoritarian, and segregational dimensions. These modernist conceptions are still present in contemporary architecture and urban planning; where in the name of modern architecture, entire communities, forms of living, and historical sites, are erased. While a critique of modernism alone is not enough, having already been conducted by postmodernism, the task of the present is, additionally, to imagine architectural forms of demodernization.

Through art exhibitions, the creation of educational environments, architectural interventions and texts written in conversation with Emilio Distretti, May Al-Dabbagh, Charles Esche, Zoe Bat and Walter Mignolo, we have started to reflect and speculate on forms of architectural demodernization. Demodernization for us does not relate to an anti-modernism, such as that expressed by reactionary, anti-technological, nationalist and fascist melancholies.

De-modernization indeed does not mean opposing the use of electricity and wiring, mortar and beams, or technology and infrastructure, nor the welfare that they can provide, channel and distribute. Instead, it means “profaning” the separations, dis-connections and isolations embodied by architectural modernism. By opposing modernity’s aggressive universalism, demodernization is a method of desegregation that applies as both discourse and praxis, to invent forms of re-appropriation and re-use of modern architecture.

After decades of work in Palestine where Decolonization essentially means the practice of opposing Israel’s regime of occupation, colonization, and apartheid, moving to Europe, via Palestine, demodernization became our the frontline in the larger struggle of decolonization, and we started to understand the “Italian southern question” more clearly as a case of internal colonization.

Needless to say, this connection is not new.

In writing the Question of Palestine, Edward Said was influenced by Antonio Gramsci´s conceptual political categories of subalternity and hegemony, developed precisely in relation to “the Italian southern question.”

Descriptions of colonized subjects, including southern Italians as backward, underdeveloped, uncivilized, lazy, and slow in catching up with modernity characterize the ideological justification for legitimizing the invasion and occupation of Libya, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia. Paradoxically, Italian settler colonialism was justified by the need to find land and work for poor southern Italians. If Gramsci was hoping for alliances between the industrialized proletariat of the north and the farmers of the south, today in a similar spirit we might call for a new alliance between southern people and immigrants. In a modest and intimate form, the work that Sandi and I have been doing together is also the result of an exploration of this possibility.

7.

In recent years, the right-wing Sicilian regional government, in an effort to relegitimize fascist policies, decided to fund the architectural conservation of the agricultural towns built by the Entity of Colonization of Sicily latifundim, restoring them as they were originally built.

Helped by modern architectural history and restoration theories that, after the second world war, cynically separated aesthetic values from social, political and economic ones, the buildings have begun to be restored as they were designed in the 1940s, reinforcing the idea that fascist architecture can exist without perpetuating fascist ideologies.

In Borgo Bonsignore for example, where the first refurbishment of the buildings began just few years ago, a new plaque appeared close to the old one commemorating the heroic gestures of patriotism (in reality crimes against humanity) of General Antonio Bonsignore, who was killed during the invasion and occupation of Ethiopia. These rural towns are all named after war and fascist criminals. Borgo Rizza, for example, was named to commemorate and remember the death of a young fascist militant.

8.

Against this nostalgic and neo-fascist approach, in Borgo Rizza (we strike out the name Rizza to negate its commemoration but at the same time not to forget what it stood for) we collaborated with the local Municipality of Carlentini, the local community, and universities to establish the Difficult Heritage Summer School, a space for critical pedagogy and discussions around practices of reappropriation and re-narration.

Over the years, we started to discuss with the local Municipality how to turn the former Entity of Colonization of Sicilian Latifundim in Borgo Rizza into an Entity of Decolonization.

This collective process has been open to all those who felt the urgency to question the broad historical, cultural and political heritage embedded in colonialism, fascism, and modernism, and therefore begin a common path towards new practices of decolonization and demodernization.

Modernist architectures, both in the former colonies and the colonizing countries, have been built as isolated sacred objects to be admired; therefore, for us, it is not enough just to reuse them in the same ways previous regimes have used them, nor to simply demolish them. They need to be profaned, to be used against themselves, and open for new common uses different from those which they were designed for.

9.

Besides the engagement on-site in Borgo Rizza, we felt the necessity to take the conversation into other contexts, to expand the possibility to learn from different sites and build new alliances.

The art installation “Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza” profanes the Entity of Colonization of the Sicilian Latifandium in Sicily, by decomposing and recomposing its facade in several modular seats. These will be reused as the platform for an open discursive space where the public is invited to critically reconsider the social, political and economic effects of fascist, colonial and modernist heritage, and at the same time collectively imagine new common uses.

The first activation of the “Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza” took place in May at the Mostra d’Oltremare in Napoli, which first opened in 1940. Conceived as a colossal exhibition to display the territories and people overseas in areas colonized by the fascist regime, it closed only 40 days after its opening, when Italy entered the Second World War. It has since had many temporary uses, including hosting refugees from the Second World War and from earthquakes in the 80s; acting as a vaccination center; and providing a venue for public events.

The second activation of “Ente di Decolonizzazione – Borgo Rizza” takes place at Hansa Quarter, in west berlin built in 1957 for the International Building Exhibition (Interbau). We are interested in exploring here how modernist architecture was deployed for the representation of a democratic Germany. Today, Interbau (1957) and the Karl-Marx-Allee are on the way to becoming UNESCO world heritage sites for their Post-war architectural and urban modernism.

Successive gatherings take place in Brussels and Albissola Marina.

This series of decolonial assemblies aims to continue our collective research by learning from different sites and by building alliances with people who feel the urgency to question modernist, colonial and fascist heritage.

In processes of colonization and decolonization, architecture plays a crucial role in organizing spatial relations and expressing ideologies. And even when abandoned or in ruins, it is still mobilized as evidence for political and cultural claims.

It is not possible to understand today’s displacement of people, flows of migration, or contemporary fascism, without a thorough knowledge of Europe’s colonial and modernist heritage.