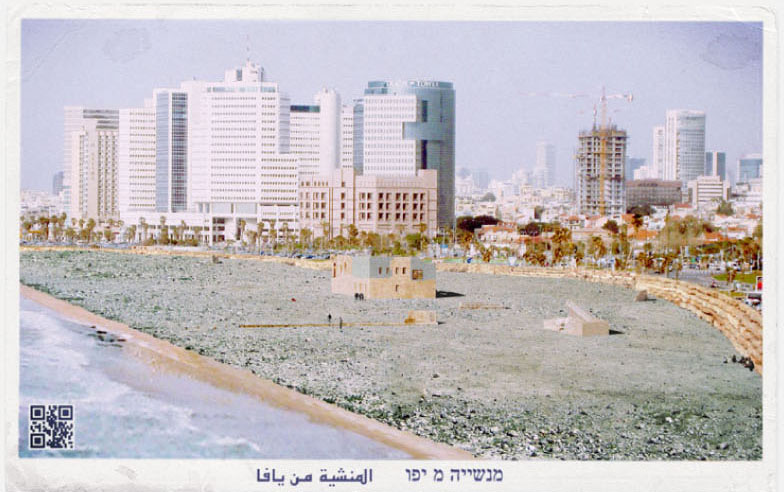

The demolitions that took place in Jaffa during the 1950s and continued until just six months ago, within meters of the Etzel Museum, are part of a veritable project to manicure the view from Jaffa’s summit to the plain of Tel Aviv. As a result, the Manshiyya neighborhood has been pulverized, transformed into a palimpsest of powder, broken stones, mortar and wood. This five-meter-deep landscape of pulverized city is today the touristic promenade of the Tel Aviv beach.

Does rubble amount to a construction material?

The tightly compressed rubble of Manshiyya’s ruins will be loosened and freed from its artificial retaining walls erected on the seashore. The rubble will be drawn out to the sea and redistributed to create a large plain along the beach. Manshiyya’s buried foundations, as well as the recent Israeli construction emerge from this rubble platform, inaugurating a place between construction and destruction.

In the context of a city, the Return will be a matter of building on the built. “The built” here refers to the Israeli construction from the past decades but also the ruins of destroyed or transformed villages. Those ruins—often imagined as an intact house in the village of origin—are today mostly disparate traces, buried or recycled scraps of former courtyards, bedrooms, and cultivated terraces. These ruins, found in all former Palestinian urban centers, are tied to the personal histories of refugees, as well as the common history of Palestine. The identification and articulation of these ruins is crucial, because a practice of Return must find ways to accomodate itself in the radically changed ‘48 areas. Ruins in this context are not only the fragments of what used to be private, but also the first tracings of what can be common.

This project, which documents the decades-long transformation of three houses in Jaffa, attempts to add to the Nakba archive developed by Walid Khalidi and Abu Sitta in their respective volumes, All That Remains (1992) and Atlas of Palestine (2004). At the same time, the archaeological investigation of these houses through media proposes the further transformation of Jaffa. Through the reconstruction of the three houses, we see that the material present is a product of a continuous reshaping. At the present time however, the traces of the Nakba appear brought to a halt, frozen in time. Ruins nevertheless are intinsically indeterminate: they have the potential to transcend melancholy and break out from their settled context. Ruins, which Ariella Azoulay writes make up the “ongoing presence” of life in destroyed Palestinian towns, as much as they embody destruction, provoke construction.