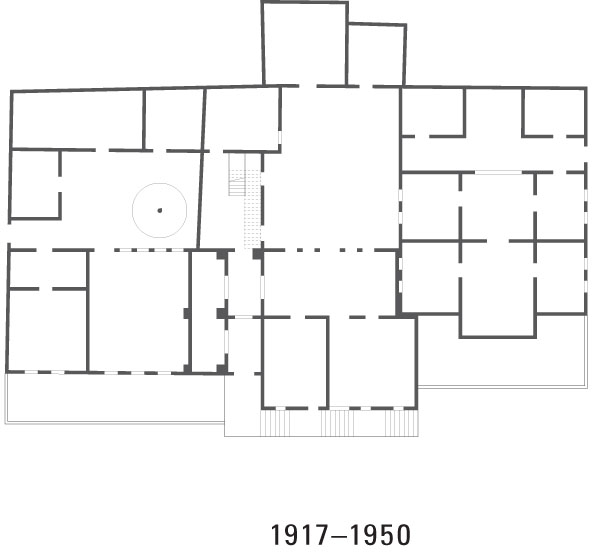

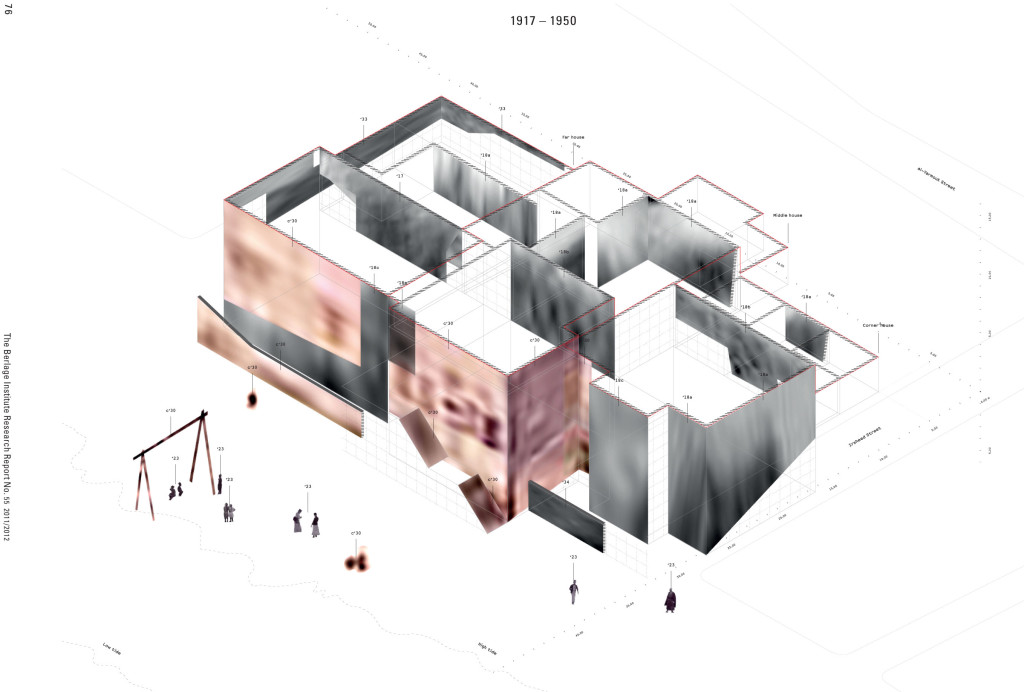

1917–1950: Beach Market

The section of the Manshiyya beach in front of these three houses was very lively. A series of wooden swing sets were installed on the beach a few meters from the edge of the high tide. Vendors took advantage of the traffic along the beach by selling ice cream and grilled meat.

Although the Tel Aviv City Council decided in 1948 to forcibly evict Manshiyya’s inhabitants and completely raze the northern blocks of neighborhoods that were adjacent to Tel Aviv, the vast majority of the buildings were spared.

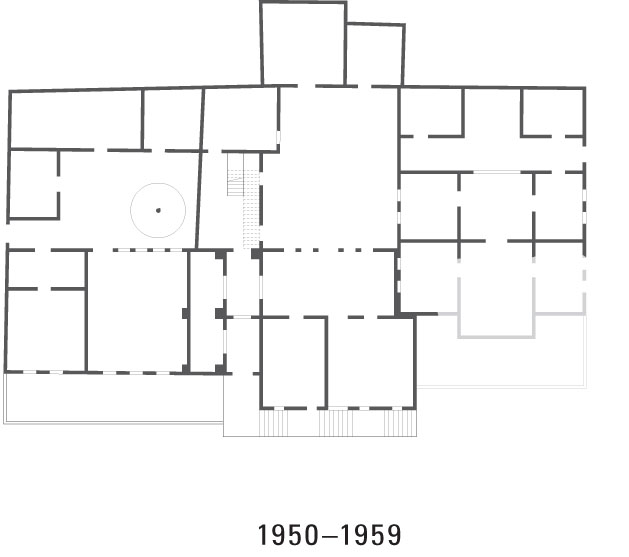

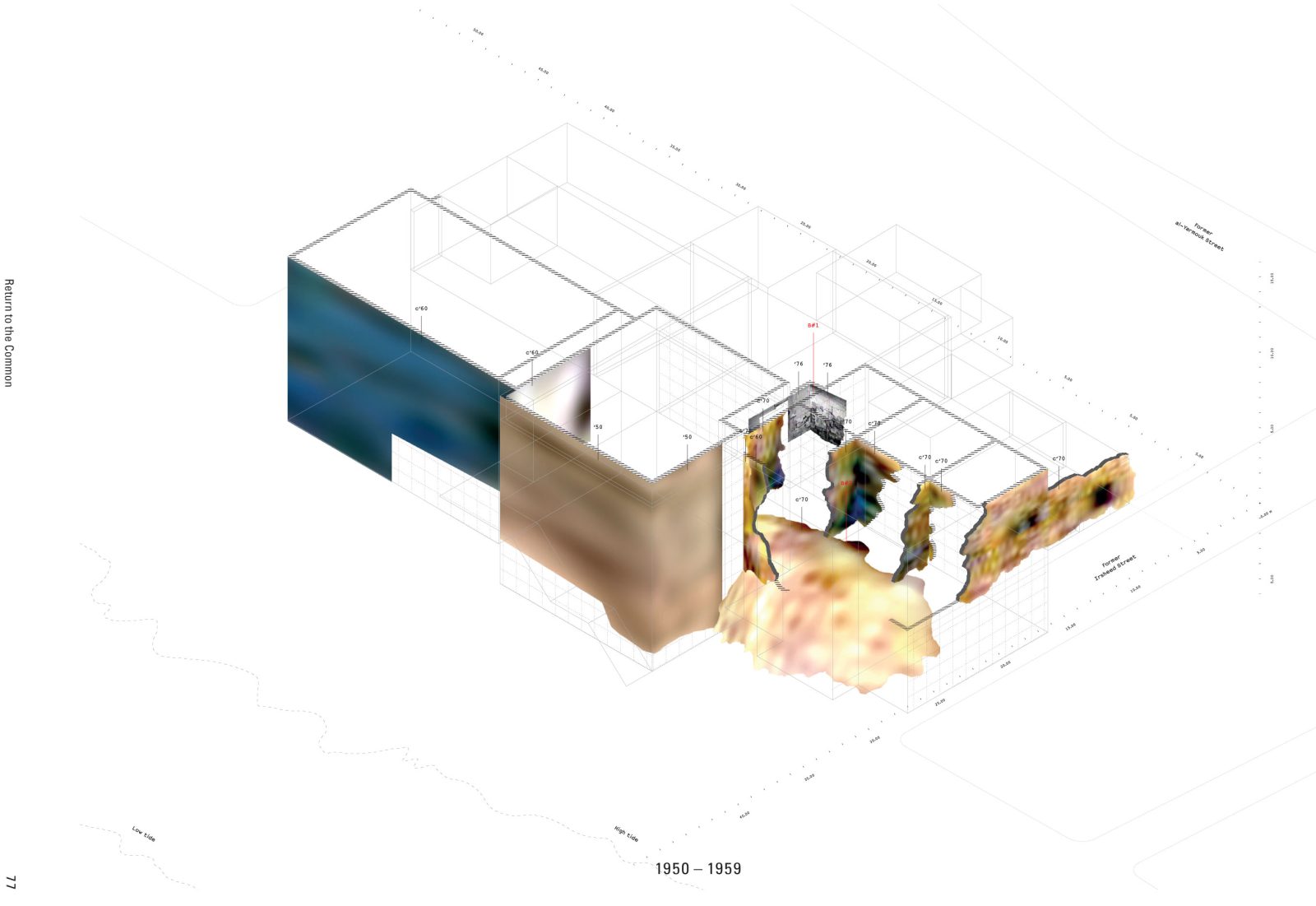

1950–1959: Vacancy

In the years immediately following the war in 1948, Manshiyya was vacant. However, in the late 50s, the abandoned buildings were taken up as a housing stock for newly arriving Jewish immigrants to Israel from Eastern Europe and Russia. The houses were squatted and divided to fit multiple families.

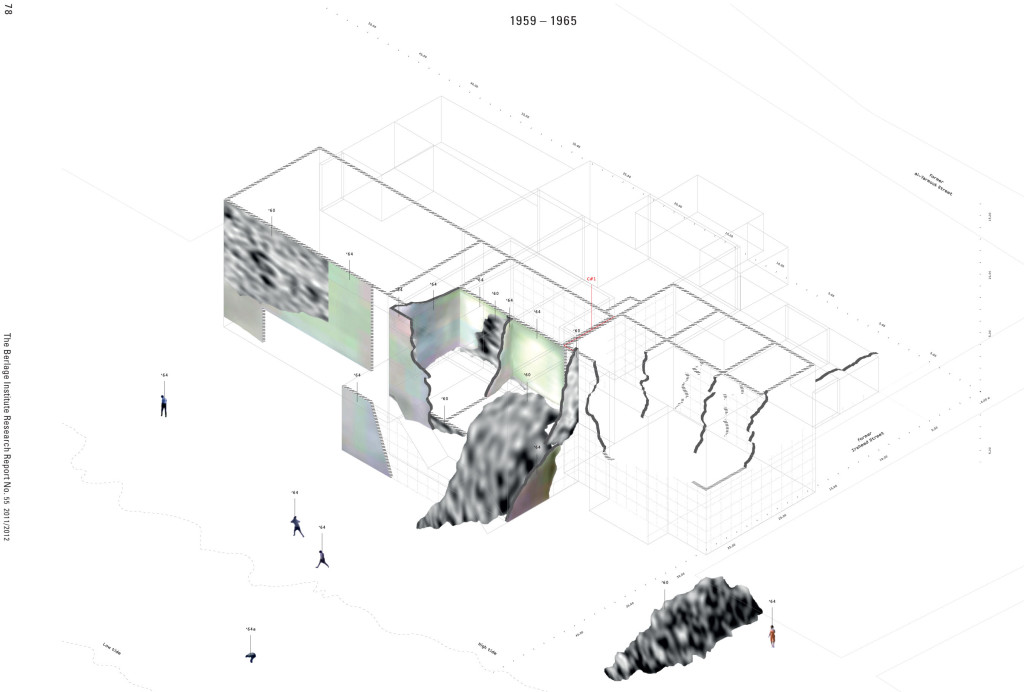

1959–1965: Tremors

Manshiyya became a squatter neighborhood that the municipality began to slowly demolish, almost room by room, courtyard by courtyard. A great volume of building debris and rubble were created as a result.

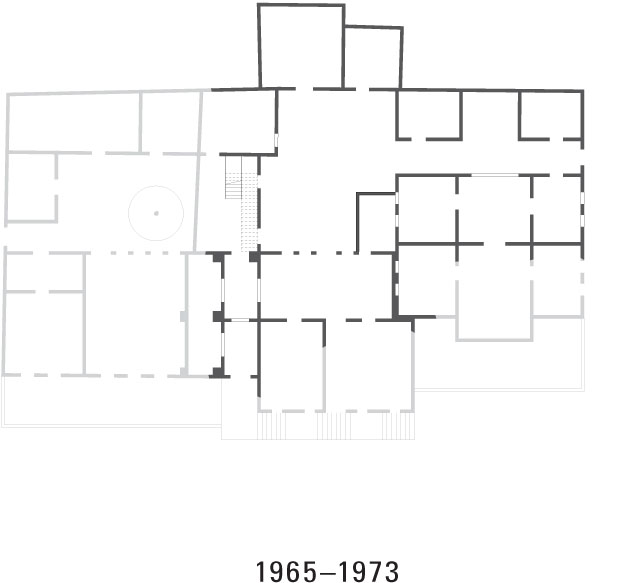

1965–1973: Rubble Landscape

The plight of those evicted from this cursed neighborhood was represented in musicals and films, such as “Kazablan,” filmed in 1973. By now the three houses are virtually swimming in the rubble of their neighbors.

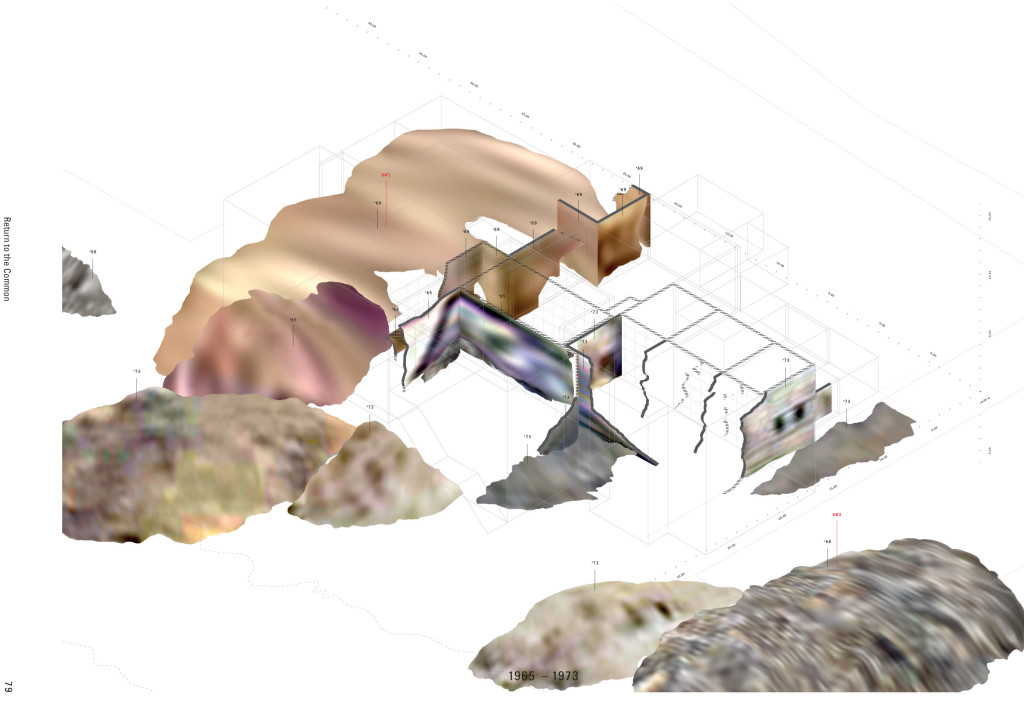

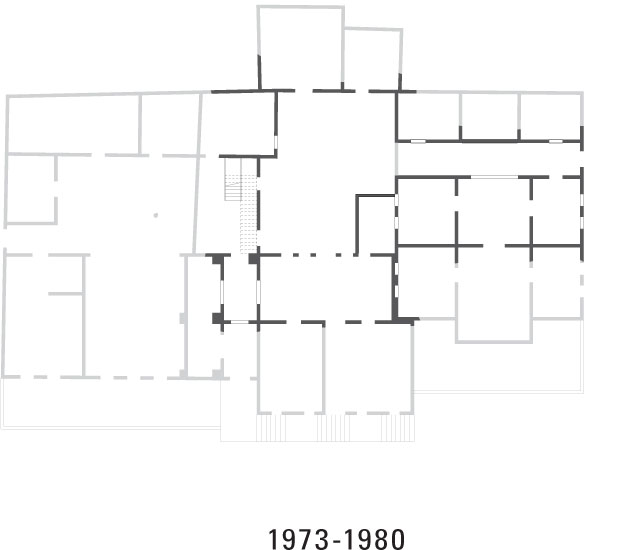

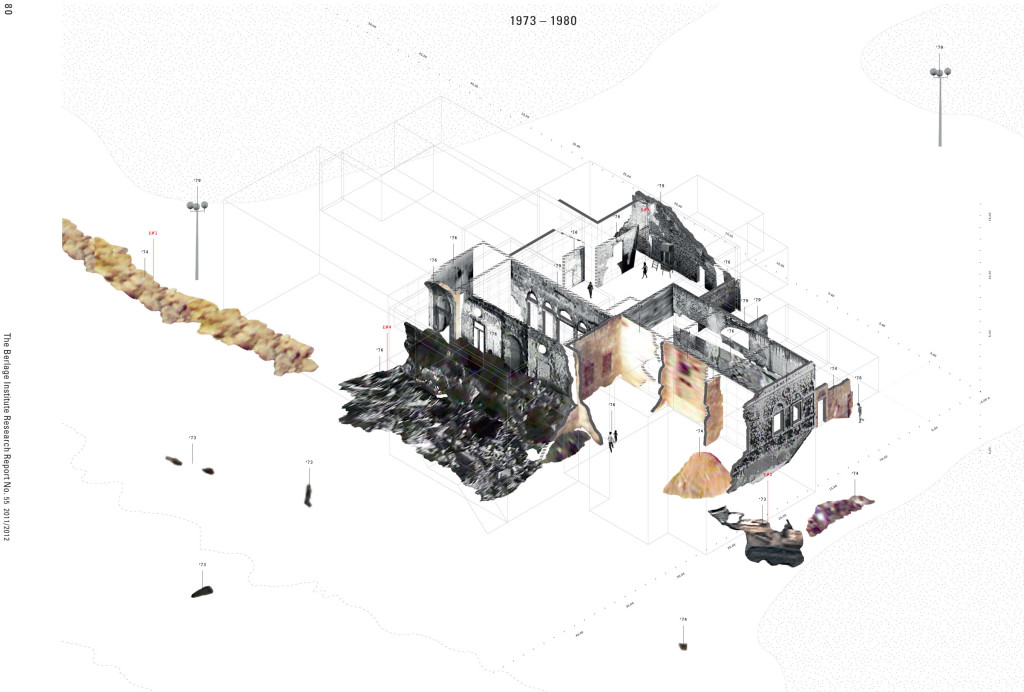

1973–1980: Maritime Burial

By the mid-1970s, the beachside landscape began to change drastically, as the rubble piled higher and higher. Eventually, the lower beach-level floors of the remaining ruins were engulfed in more than four meters of granulated remains from disfigured neighboring structures. Here, urbanism is—in the words of a famous painter—a sum of destructions.

It was in this period that the three architects came to the site and imagined the design of the Etzel Museum. When the architects visited the site, they met a family of immigrants from Eastern Europe who were inhabiting the ruins.

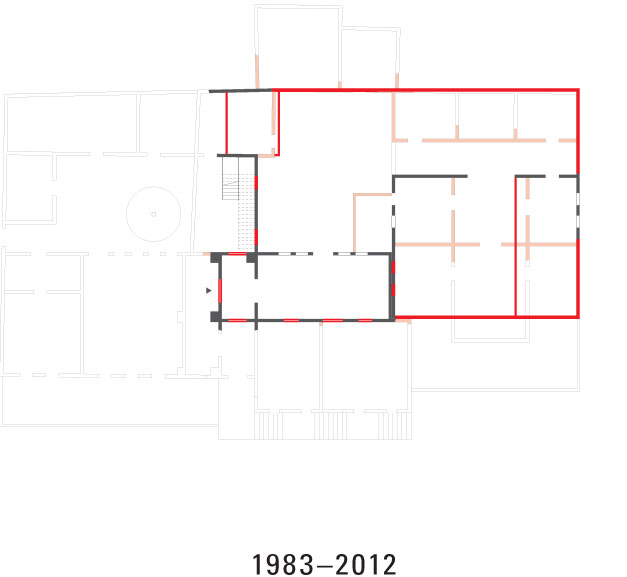

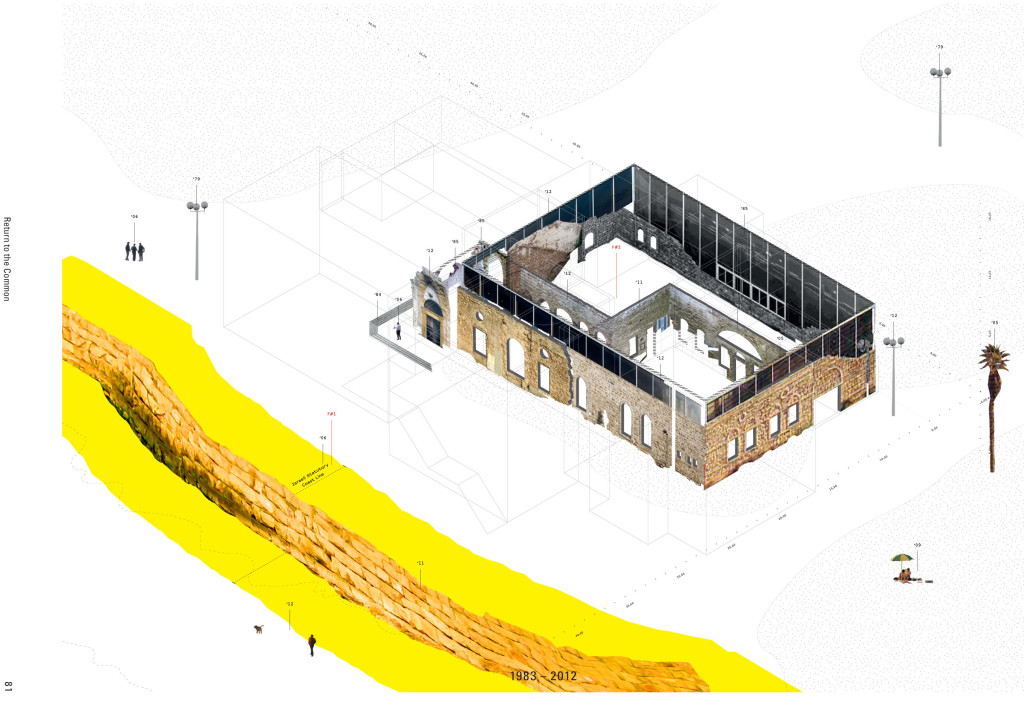

1983 – 2012: Military Archaeology

The architects, the IDF Museum Unit, and the Israel Antiquities Authority uphold the testimonial account of a Jaffan Jew who maintains that the ruins constituted a single building constructed in 1900 under the charge of a Russian Zionist. The design of the Etzel Museum indeed evokes the image of a single building: its surmounting, dark crystalline shell rises from the low, stone-veneer walls, “freezing time” and “schematically completing the building to what it was,” in the architects’ words. Considering Jaffa’s characteristic density, it is remarkable that the architects insisted that these ruins, which were in the company of numerous other ruins along the beach, represented the remains of a one, independent building. By their account, the ruins were an isolated, naturally- weathered object. Their narrative, and indeed the Etzel Museum as it was built, represents a version of history devoid of the urban fabric of Jaffa, becoming a harmless vestige.

Niv’s team pledged to do their “best to respect the remains”. Paradoxically, in order to construct the museum they foresaw, the architects had to destroy many of the ruined walls that remained there. The so-called preservation of the ruins congealed the disparate building fragments together, creating the image of a single, officially “well-preserved” Zionist house. Taking into account the Israeli Antiquities Authority’s principal goal to “preserve all elements in situ”, here one sees architecture exposing the inherent schizophrenia of colonialism.