In 1940, the Fascist regime established the “Entity of Colonization of Sicilian Latifundia / Ente di Colonizzazione del Latifondo Siciliano” following the model of the “Entity of Colonization of Libya” and colonial architecture in Eritrea and Ethiopia. These territories were considered by the regime “empty,” “underdeveloped,” and “backward” and therefore in need to be “reclaimed,” “modernized,” and “repopulated.” For this purpose, the “Entity of Colonization” inaugurated in Sicily eight new rural towns and as many remained unfinished. Today most of these villages have fallen into ruin.

In 1940, the Fascist regime established the “Entity of Colonization of Sicilian Latifundia / Ente di Colonizzazione del Latifondo Siciliano” following the model of the “Entity of Colonization of Libya” and colonial architecture in Eritrea and Ethiopia. These territories were considered by the regime “empty,” “underdeveloped,” and “backward” and therefore in need to be “reclaimed,” “modernized,” and “repopulated.” For this purpose, the “Entity of Colonization” inaugurated in Sicily eight new rural towns and as many remained unfinished. Today most of these villages have fallen into ruin.

However, what does not seem to be in ruin in Italy is the persistence of colonial and fascist rhetoric, culture, and politics. Despite the fall of fascism following the Second World War, Italy’s de-fascistization remains an unfortunately unfinished process. This is one of the reasons why Italy still has visible architectures, monuments, plaques, and toponymy that celebrate the fascist regime. Furthermore, Italy – having lost its colonies during the Second World War – has never embarked on a real process of decolonization.

In 2017, the nomination of Asmara, the capital of Eritrea, as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for its fascist and colonial architecture built during the period of Italian occupation, posed a series of fundamental questions for both the ex-colonized and the ex- colonizers: who has the right to preserve, reuse and re-narrate fascist colonial architecture?

The installation presented for the 2020 Quadriennale d´arte- FUORI at Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, home to the First International Colonial Art Exhibition (1931) and other propaganda exhibitions of the regime, proposes to rethink the rural towns built by the “Entity of Colonization” in Sicily starting from the nomination of Asmara as a World Heritage Site. The installation is the first intervention ”Towards a Decolonization Entity / Verso un Ente di Colonizzazione” that will be made up of those who feel the urgency to question the broad historical, cultural and political heritage steeped in colonialism and fascism, and thus begin a common path towards new practices of decolonization and reparation.

The installation presented for the 2020 Quadriennale d´arte- FUORI at Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome, home to the First International Colonial Art Exhibition (1931) and other propaganda exhibitions of the regime, proposes to rethink the rural towns built by the “Entity of Colonization” in Sicily starting from the nomination of Asmara as a World Heritage Site. The installation is the first intervention ”Towards a Decolonization Entity / Verso un Ente di Colonizzazione” that will be made up of those who feel the urgency to question the broad historical, cultural and political heritage steeped in colonialism and fascism, and thus begin a common path towards new practices of decolonization and reparation.

TOWARDS AN ENTITY OF DECOLONIZATION/ VERSO UN ENTE DI DECOLONIZZAZIONE, 2020

A project by Sandi Hilal e Alessandro Petti (DAAR)

Photograpohic dossier: Luca Capuano

Installation: Video projections, Photographs, plexiglass

Research and text: Emilio Distretti, Husam Abu Salem

Graphic design: Diego Segatto, Rosanna Lama

QUADRIENNALE D’ARTE 2020 | FUORI

Palazzo delle Esposizioni, Roma

30 Ottobre 2020 > 17 Gennaio 2021

Borgo <del>Bonsignore</del>

Data di costruzione: inizio lavori gennaio 1940 / fine lavori 1940

Riferimento del nome del borgo: Antonio Bonsignore (ha preso parte alla guerra d’Etiopia) Architetto/ingegnere: Donato Mendolia

Possibile tipologia di borgo: Tipo A

Distretto: Comune di Ribera, provincia di Agrigento

Coordinate: 37°25’18.8”N 13°16’11.7”E

Proprietario del terreno prima della costruzione: ospedale civico di Sciacca (in gran parte)

Valore terreno al momento della costruzione: £ 1.551.837,0

Costi di costruzione: £ 1.303.505,10

Stato attuale: Varie ristrutturazioni e aggiunte / disabitato

Photogrphic dossier: Luca Capuano

fonti Archivio Luce: www.patrimonio.archivioluce.com

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borgo_Bonsignore

https://wwwvoxhumana.blogspot.com/03/2013/la-via-dei-borghi-12la-quinta-fase-dei.html https://www.fondoambiente.it/luoghi/borgo-bonsignore?ldc

Borgo <del>Schirò</del>

Data di costruzione: fine lavori dicembre 1940

Riferimento del nome del borgo: Giacomo Schirò

Architetto/ingegnere: Girolamo Manetti-Cusa

Possibile tipologia di borgo: Tipo A

Distretto: Comune di Monreale, provincia di Palermo

Coordinate: 37°29’48.8”N 14°12’00.6”E

Proprietario del terreno prima della costruzione: famiglie Mirto, Riina, Terrusa, Gennaro e Chiaramonte

Valore terreno al momento della costruzione: £ 2,405,945.0

Costi di costruzione: £ 4,620,024.68

Stato attuale: cattive condizioni, ristrutturazioni limitate, graffiti su molti edifici

Popolazione: 0 (dati relativi al 2011)

fonti Archivio Luce: www.patrimonio.archivioluce.com

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borgo_Schir%C%3B2

http://wwwvoxhumana.blogspot.com/search/label/borgo20%Schir%C%3B2

https://www.vacuamoenia.net/it/portfolio/borgo-schiro/

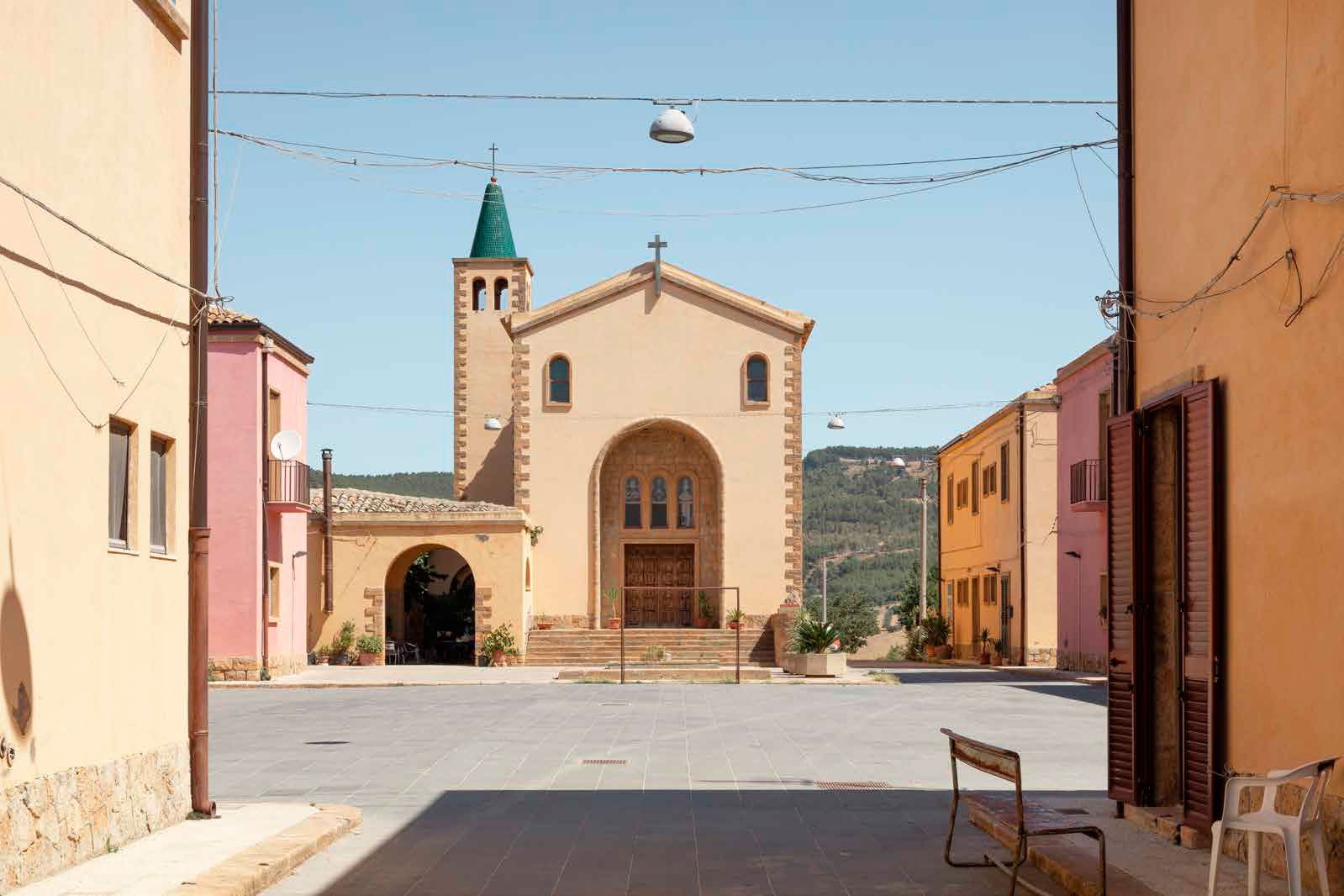

Borgo <del>Cascino</del>

Date of construction: 1940

Name: Antonio Cascino participated in the occupation of Albania and Slovenia

Population: 47

Architect: Giuseppe Marletta

Typology: A

Provance: Enna

Coordinate: 37°29’48.8”N 14°12’00.6”E

Landowners before the construction: Famiglie Greco-Militello e Lo Manto

Actual status: Renovated in 2004

Notes from the field

This was the first town we visited in our fieldwork. In the square, we met a welcoming old couple. (conversation link). They talked about a continuously inhabited town as an extended family.

The town was given to the local municipality from the “Ente dello sviluppo” with the requirement that the buildings should have a permanent public use. At the time of the visit, the public buildings have been transformed into housing. And although they don’t have any recognized ownership, they don’t’ feel the fear of being evicted.

The town has been recently renovated in 2004 (“Lavori di sviluppo e rinnovamento” Ministero delle politiche agricole alimentari e forestale, fondo europeo agricolo per lo sviluppo rurale, programma di sviluppo rurale, Enna Municipality).

A plaque entitled to Antonio Cascino , a soldier who died in the war of 1917.

The town is designed around the piazza, a void created by the facades of public institutions. What is this void? The facades and the piazza are very photogenic. It is not surprising that local photographers use it as a location for weddings.

Photogrphic dossier: Luca Capuano

Data di costruzione: inizio lavori febbraio 1940 / fine lavori dicembre 1940

Riferimento del nome del borgo: Antonio Cascino (ha partecipato alla colonizzazione di Albania e Slovenia)

Architetto/ingegnere: Giuseppe Marletta

Possibile tipologia di borgo: Tipo A

Distretto: Provincia di Enna

Coordinate: 37°29’48.8”N 14°12’00.6”E

Proprietario del terreno prima della costruzione: Famiglie Greco-Militello e Lo Manto

Valore terreno al momento della costruzione: £ 1,842,224.0

Costi di costruzione: £ 1,323,645.0

Stato attuale: Varie ristrutturazioni ed aggiunte. Parzialmente abitato

Popolazione: 47 (dati relativi al 2011)

fonti Archivio Luce: www.patrimonio.archivioluce.com

https://sh.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borgo_Cascino,_Enna

https://www.ennamagazine.it/News/TabId/92/ArtMID/490/ArticleID/2270 http://wwwvoxhumana.blogspot.com/05/2013/la-via-dei-borghi-15la-quinta-fase-dei.html https://www.vacuamoenia.net/it/portfolio/borgo-cascino/

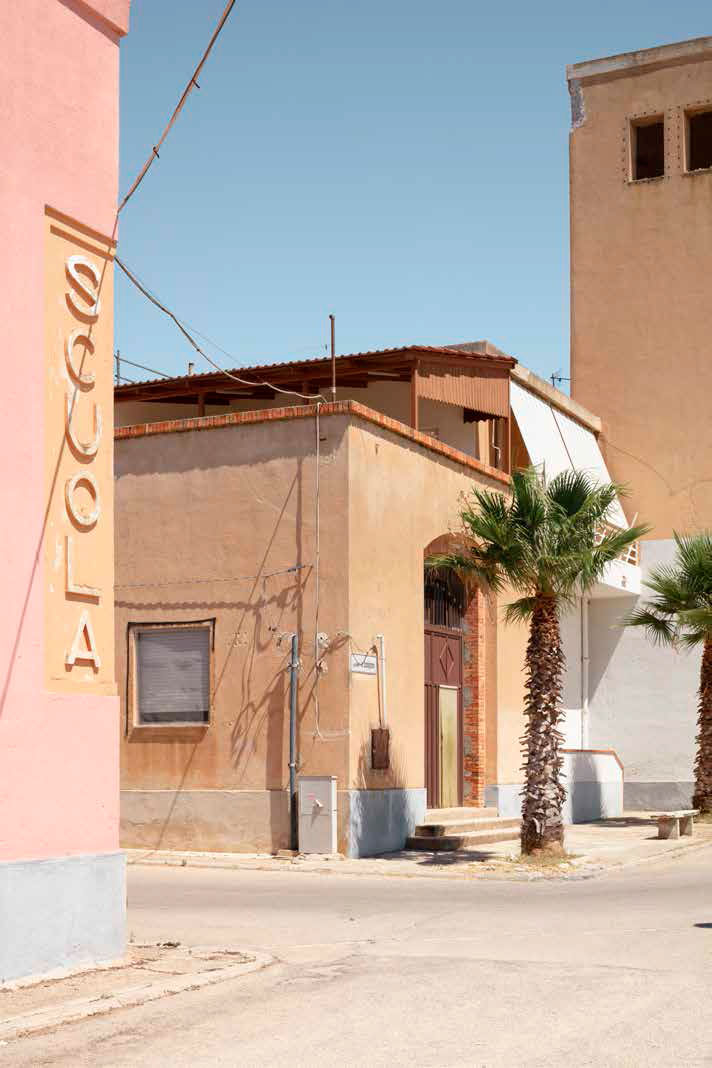

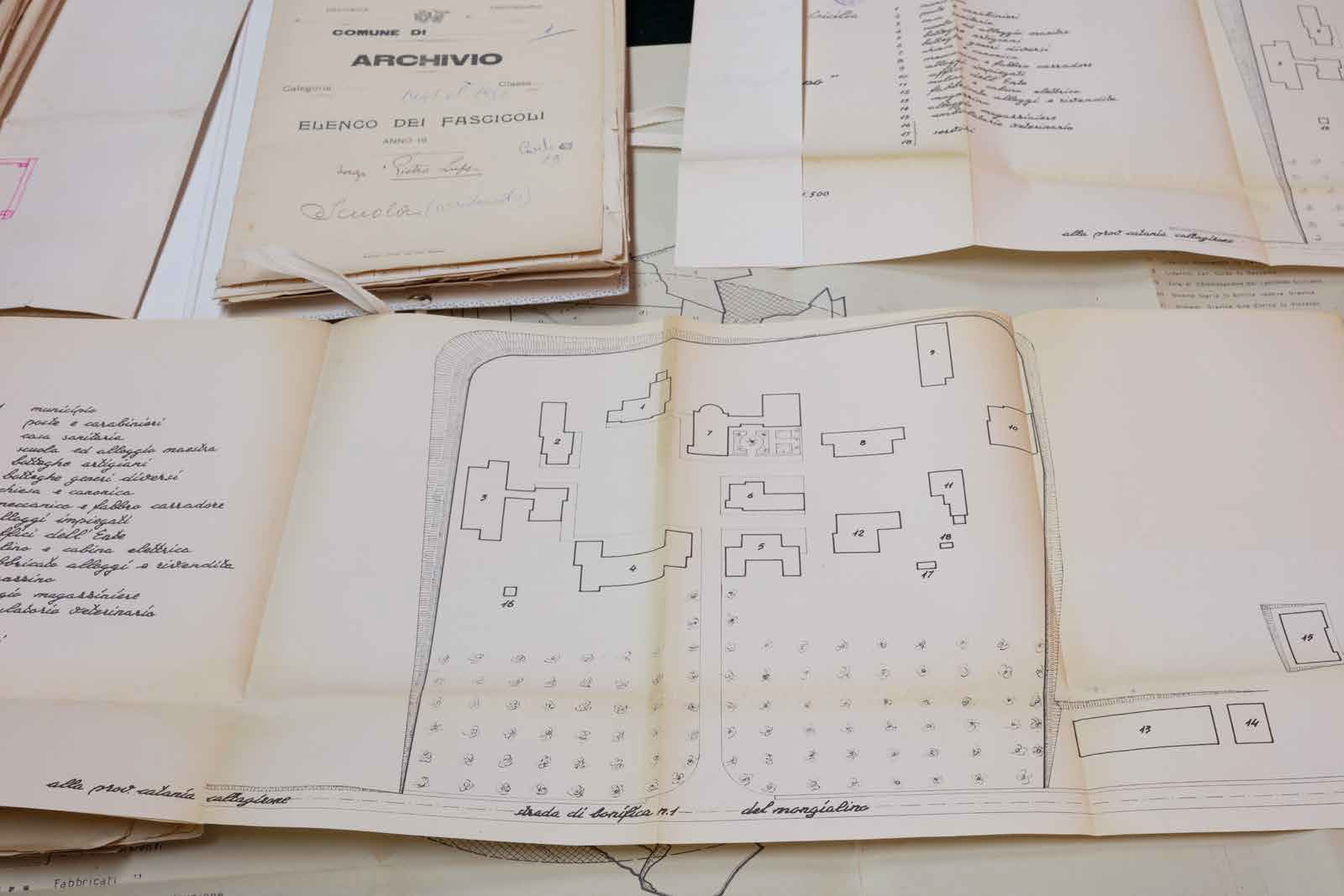

Borgo <del>Lupo</del>

Data di costruzione: inizio lavori gennaio 1940 / fine lavori dicembre 1940

Riferimento del nome del borgo: Pietro Lupo (ha partecipato alla guerra in Africa)

Architetto/ingegnere: Filippo Marino

Possibile tipologia di borgo: Tipo B

Distretto: Comune di Mineo, provincia di Catania

Coordinate: 37°20’30.4”N 14°37’34.3”E

Proprietario del terreno prima della costruzione: probabilmente famiglia Giusino

Valore terreno al momento della costruzione: N.A.

Costi di costruzione: £ 1,865,938.30

Stato attuale: diverse ristrutturazioni

Popolazione: 15 (dati relativi al 2019)

fonti Archivio Luce: www.patrimonio.archivioluce.com

http://wwwvoxhumana.blogspot.com/search/label/Borgo%20Lupo

https://www.vacuamoenia.net/it/portfolio/borgo-lupo/

https://www.gettyimages.com/detail/news-photo/view-of-the-central-square-of-borgo-pietro-lupo-built-news-photo/482271325

Borgo <del>Fazio</del>

Data di costruzione: inizio lavori gennaio 1940 / fine lavori dicembre 1940

Riferimento del nome del borgo: Amerigo Fazio (ha partecipato alla colonizzazione dell’Eritrea)

Architetto/ingegnere: Luigi Epifanio

Possibile tipologia di borgo: Tipo B

Distretto: Comune di Guarine, provincia di Trapani

Coordinate: 37°51’26.3”N 12°40’03.5”E

Proprietario del terreno prima della costruzione: N. A.

Valore terreno al momento della costruzione: N.A (i proprietari rifiutarono di vendere e aprirono una causa civile)

Costi di costruzione: £ 1,502,319.0

Stato attuale: abbandonato, rovine

Popolazione: 0

fonti Archivio Luce: www.patrimonio.archivioluce.com

http://wwwvoxhumana.blogspot.com/04/2013/la-via-dei-borghi-13la-quinta-fase-dei.html

https://www.vacuamoenia.net/it/portfolio/borgo-fazio/

Borgo <del>Giuliano</del>

Data di costruzione: inizio lavori gennaio 1940 / fine lavori dicembre 1940

Riferimento del nome del borgo: Salvatore Giuliano (ha preso parte alla colonizzazione dell’Eritrea)

Architetto/ingegnere: Guido Baratta

Possibile tipologia di borgo: Tipo A

Distretto: Provincia di Messina

Coordinate: 37°49’15.5”N 14°41’10.0”E

Proprietario del terreno prima della costruzione: Leanza Amato

Valore terreno al momento della costruzione: £ 1,280,539

Costi di costruzione: £ 1,287,923

Stato attuale: totalmente abbandonato, rovine

Popolazione: 0 (dati relativi al 2011)

fonti Archivio Luce: www.patrimonio.archivioluce.com

http://wwwvoxhumana.blogspot.com/search/label/Borgo%20Giuliano

https://www.vacuamoenia.net/it/portfolio/borgo-giuliano/

Borgo <del>Petilia</del>

Date: 1940

Name: Originally named Borgo Gigino Gattuso

Population: 85

Architecture: Edoardo Caracciolo

Tipology: Tipo A

provance: Caltanissetta

Coordinate: 37°32’35.0”N 14°03’37.0”E

Actual status: partially renewed

Notes from the fieldwork

The town is more modest compared to others. The community is quite active: they renovated the church and other buildings. A museum of the farmer civilization aims “through territorial marketing, give values to local cultural, identity, tradition and local food with the activation of a web site for tourists”.

It was previously named Gigini Gattuso, a fascist militant protagonist also of one of Camilleri novel, “Privo di Titolo”.

The main building was heavily transformed.

Photographic dosser Luca Capuano

Data di costruzione: inizio lavori gennaio 1940 / fine lavori dicembre 1940

Riferimento del nome del borgo: Il borgo originariamente era stato chiamato Borgo Gigino Gattuso

Architetto/ingegnere: Edoardo Caracciolo

Possibile tipologia di borgo: Tipo A

Distretto: Comune di Caltanissetta, provincia di Caltanissetta

Coordinate: 37°32’35.0”N 14°03’37.0”E

Proprietario del terreno prima della costruzione: N.A.

Valore terreno al momento della costruzione: N.A.

Costi di costruzione: £ 1,267,226.60

Stato attuale: parzialmente ristrutturato

Popolazione: 85 (dati relativi al 2011)

fonti Archivio Luce: www.patrimonio.archivioluce.com

http://wwwvoxhumana.blogspot.com/search/label/borgo%20Petilia

http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Borgo_Petilia