Naji Odeh, Director of Al Feneiq Center

…we need to think about a model for the return… Al Feneiq is a Novel that we have created, it represents a collective cultural process able to innovate, change and reverse itself. Indeed the first Feneiq was created in Deheishe, but we succeeded also to create another center in Aroab camp… a Feneiq could be created also in Deir Aban, my village of origin…

I know that finally a Feneiq in my village would be even stronger than the Feneiq in Deheishe camp… I will leave Deheishe Camp to the city of Bethlehem. I know I will miss Deheishe, I will return back to walk in its alleys in the summer nights… Bethlehem will remain the place where I will gather my forces and my people to prepare a new basis and a new life for the Return.

I’m sure we will be able to reproduce a model through the collective work that will not only prepare the environment for the return, but that will influence the whole Arab world…

Al Feneiq, Deheishe camp 24.08.2009

Return has thus a simultaneous material effect in both the sites of origin (Palestine) and sites of displacement. The result might be a reciprocal extraterritoriality that connects these two sites: both kept apart, both transferred to common use.

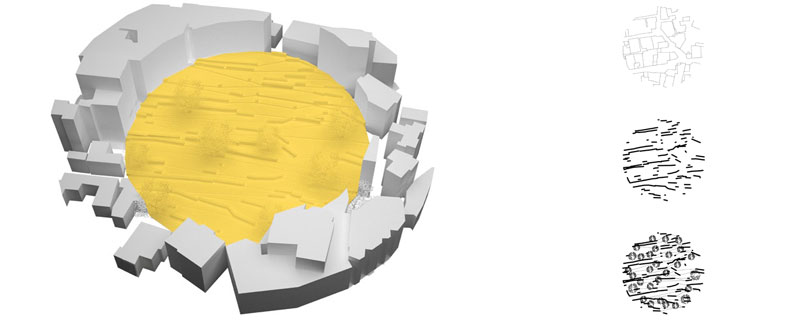

It is between these two sites of reciprocal extraterritoriality that the proposal floats. We take a circular probe from both camp and village, and each is explored as a site of possible physical interventions.

Extract from Lieven de Cauter, Palestinian diary

…I insisted that I definitely wanted to see Al Feneiq (the Phoenix), a cultural centre built by the camp residents. We drove around the camp and came to the hill overlooking the slope of the camp and the surrounding landscape. When we parked our car a crowd was flocking around a big building.

Sandi explained that the Palestinian Authority wanted to make a prison here on the top of the camp, but the residents had resisted it and had finally squatted the ground to make their cultural centre.

Then she insisted we gather to make a tour with the director of Al Feneiq, Naji, a slim, kind man with a weathered face and big black moustache. He showed us the whole place with the humble pride of a master of the house. Besides a big hall for all sort of events on the ground floor, it had several levels, and one more to come.

It had a fitness room with real parquet floor (just laid as we came, they were still polishing it), a theatre hall, a ballet room, class rooms for after school lessons, offices, an exhibition hall and even rooms for visitors. Next to the building there was a closed garden, for a little money you could enter it (one shekel for youngster, two shekel for adults). We didn’t, but from the roof, it really looked like a closed garden, an artificial Eden, a claustrum for quiet recollection and meditation. Great idea, for it was not a park you just cross, it was something special: a real paradise garden in the anthropological sense.

The roof was one big terrace giving a panoramic vista on the whole of Bethlehem territory. Naji insisted that the roof was an important place too: you could explain to visitors the whole situation, or give receptions and gatherings, or just enjoy the view. On the roof I asked Naji the big overall questions: why all this, what was at stake for him in this project?

‘We had to do something, we had to give hope to the next generation, many of us were in prison for several years, I was in prison, but we have to give hope to the young. It is our centre, it is our work, stone by stone this centre was build by camp residents. We make groups for 20 days and then another group of workers comes. So we supply work. And pride. Everybody wants to help. Everybody is proud of this. It gives hope to the youngsters and it gives them an education, culture and leisure.’

By this time I could hug the man, but I didn’t. I was really impressed by this centre and by their power – and I think also his power – to create this out of nothing. Never before had I seen the power of heterotopia so clearly… I said it was very political but in an indirect way.

Naji was pleased and said yes: ‘This is political work, but in another way.’ I congratulated him on this project. ‘But does it not preclude the idea of return by making something for people to settle for, to really settle I mean?’ Here he looked at me and was firm: ‘For me that does not change anything. If I could go back, I would go back immediately, on my own. If I have no place to stay, I would sleep under a tree, no problem. My wife and my children could join me, or stay here, but I would go.’