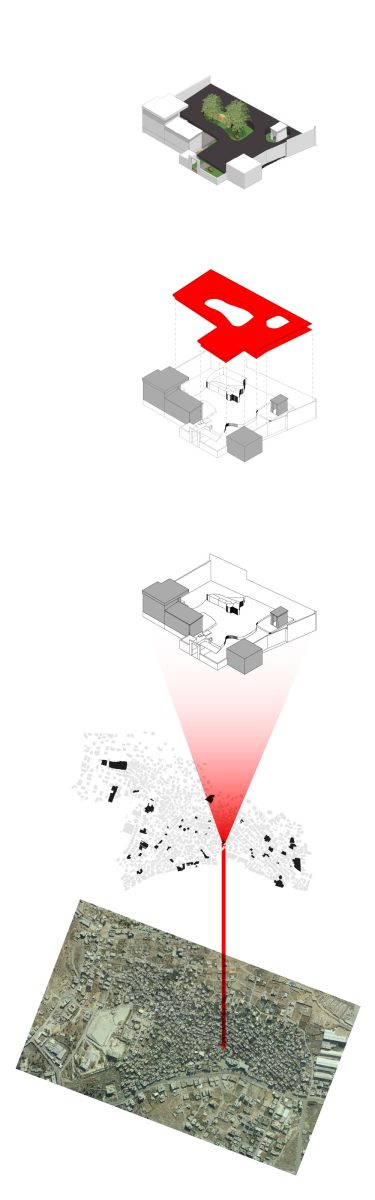

The Concrete Tent deals with the paradox of a permanent temporariness. It solidifies a mobile tent into a concrete house. The result is a hybrid between a tent and a concrete house, temporariness and permanency, soft and hard, movement and stillness.

The project tries to inhabit the paradox of how to preserve the very idea of the tent as symbolic and historical value. Because of the degradability of the material of the tents, these structures simply do not exist any more. And so, the re-creation of a tent made of concrete today is an attempt to preserve the cultural and symbolic importance of this archetype for the narration of the Nakba, but at the same time to engage the present political condition of exile.

Photo by Sara Anna

The Concrete Tent is a gathering space for communal learning. It hosts cultural activities, a working area and an open space for social meetings. The urgency and idea of such a space emerged in discussion with the participants of Campus in Camps who saw a possibility to materialize and give architectural form to narrations and representations of camps and refugees beyond the idea of poverty, marginalization and victimization.

The Concrete Tent has become a site of exchange, debates and self-reflection and has quickly taken the role as a gathering place. Youth are using it as meeting point, newlyweds have found the tent to be a good place to celebrate and are taking their wedding pictures in front of the curious architecture, negotiators from the camp are using it for peace resolution meeting among families, social and cultural events are happening.

When we think about refugee camps one of the most common images that come to our mind is an aggregation of tents. However, after more than sixty years since their establishment, Palestinian refugee camps today are constituted by a completely different materiality. Tents were first reinforced and readapted with vertical walls, later substituted with shelters, and subsequently new houses made of concrete were built, making camps dense and solid urban spaces.

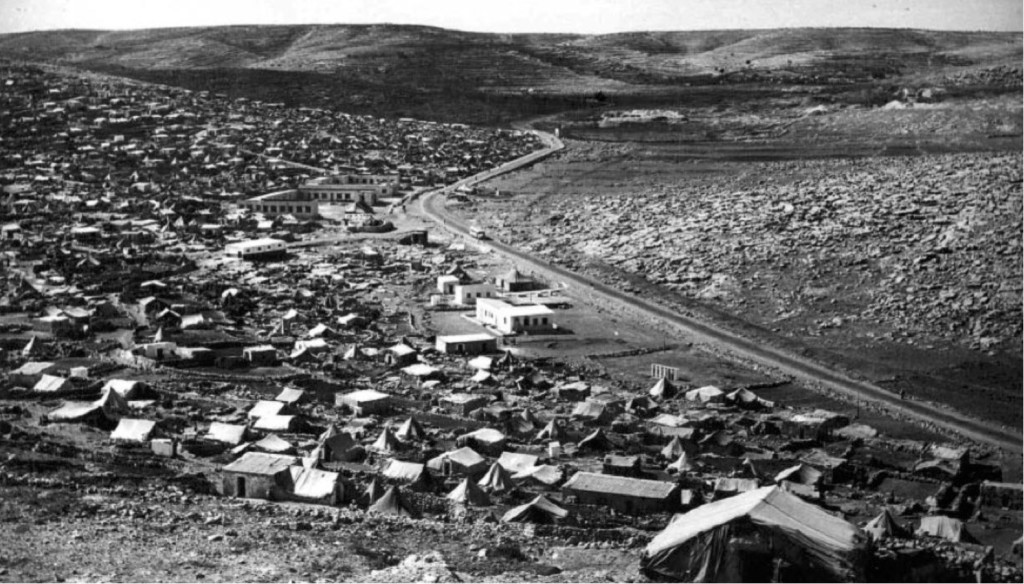

Dheisheh refugee camp, 1952 (UNRWA archive)

Dheisheh camp was created in 1949 to offer shelter to the Palestinian families expelled from 45 villages around Jerusalem and Hebron areas. At that time refugees first gathered in the open land on the margins of the city of Bethlehem, where UNRWA provided families with tents. By the middle of the 1950s, UNRWA built shelters, each family received a 9 square meter shelter and every 15 families shared one bathroom.

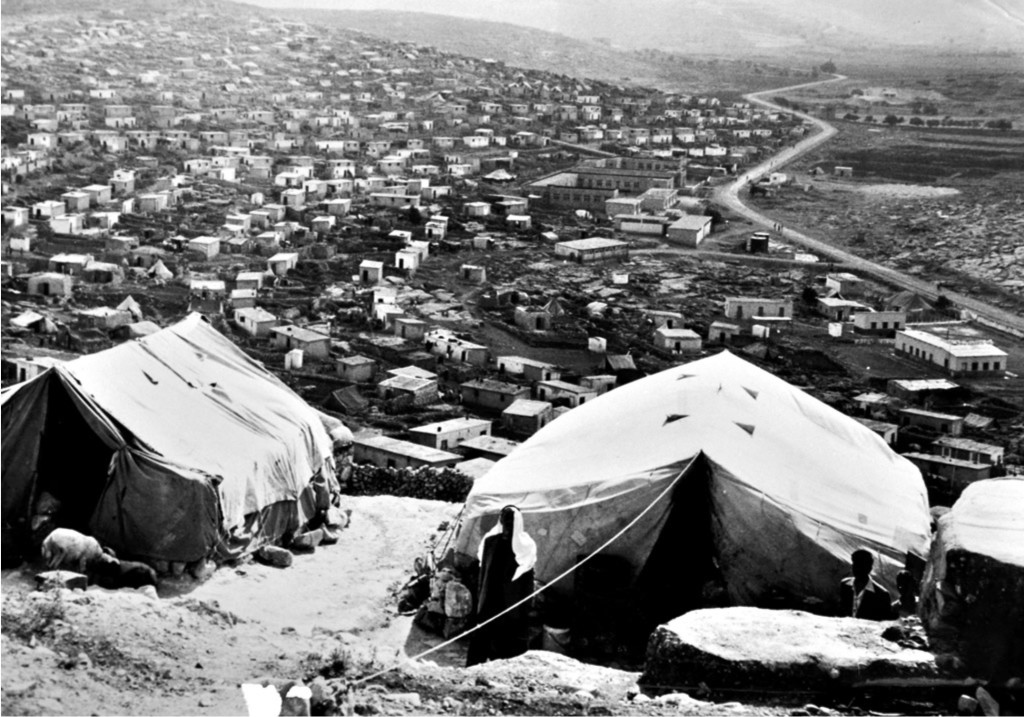

Dheisheh refugee camp, 1959 (UNRWA archive)

The land where camps are located are leased by UNRWA from host governments. According to UNRWA’s rules and regulations, the property may not be rented, sold, or transferred to others by the refugees and UNRWA does not recognize any sale or lease by the refugees. Despite these regulations, there exists a de facto selling, buying, renting and leasing of camp land and property. This process has existed since the establishment of the camp.

There are 59 refugee camps scattered between Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, West Bank and Gaza. Officially UNRWA (The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) does not administer camps since its mandate is to provide relief and works programmes for Palestine refugees. In reality after almost 70 years since the agency has been established it has been forced to expand its role and has been challenged by refugees to move beyond humanitarianism.

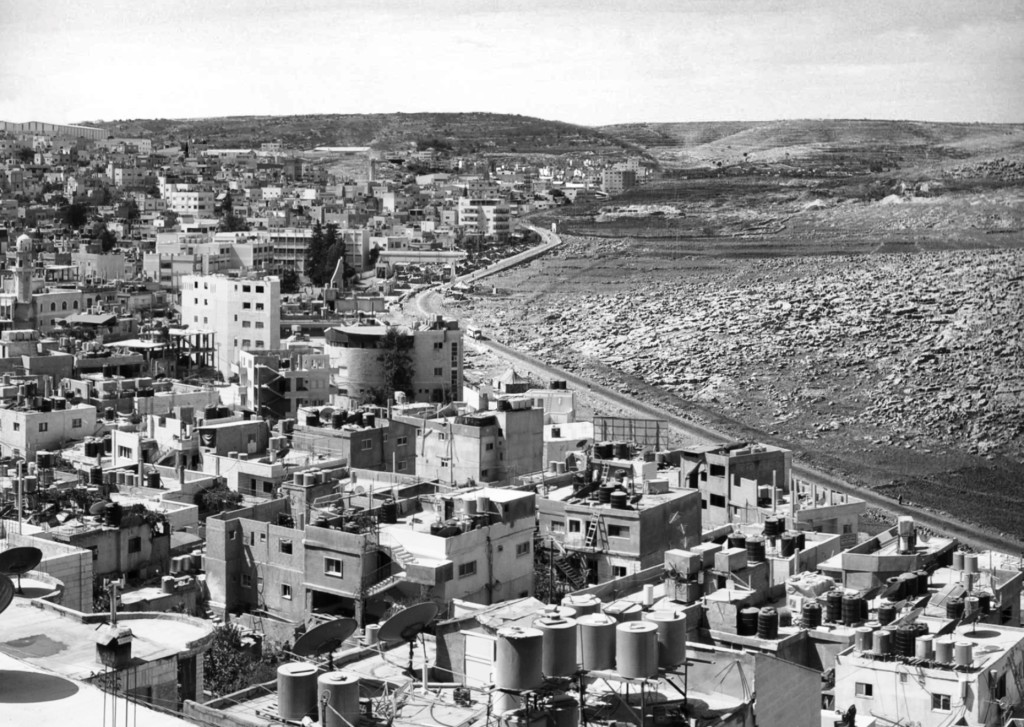

Dheisheh refugee camp, 2011 (Brave New Alps)

Dheisheh camp today hosts 13.000 people. With time the camp has become overcrowded and a very dense urban space with no public space. Refugees have been always reduced to individual numbers in statistics, rarely considered as a collective community with its own need for collective spaces besides the need of sheltering.

In camps, legally, public or private property does not exist. Since the land is leased by UNRWA from the government, refugees can not even own their houses. UNRWA is also not a municipality that takes responsibility of collective spaces (despite providing similar services of a municipality such us collective garbage, providing building regulations, etc…).

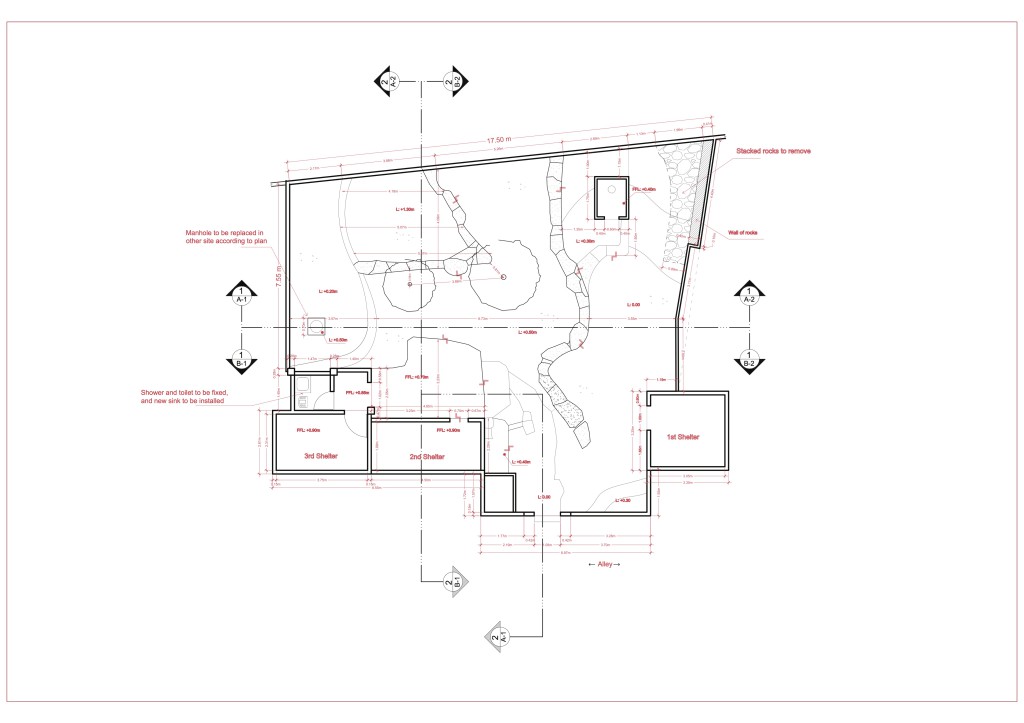

In 2013 Campus in Camps participants started to map out the unbuilt spaces in Dheisheh refugee camp (The Unbuilt) discovering an intricate matrix of open spaces. By mapping the unbuilt, Campus in Camps participants were searching for a site for a collective intervention. They found a plot, now belonging to the Al-lahham family, consisting of 3 shelters, one shared bathroom and a water reservoir.

The three shelters site consisted of three original 1950s UNRWA-built structures (three rooms, one latrine and a water reservoir) that were still standing. This small plot contains several historical periods in the development of the camp: rocks and olive trees (the site as known by refugees when they first arrived in 1949), the shelters built by UNRWA to replace the worn tents, the public toilet, and new buildings. In addition to the “historical relevance”, this site contains the material evidence of a particular communal life that exists in the camp.

In December 2013 after surveying the project site, a collaborative design process unfolded among the residents, Campus in Camps participants and DAAR.

Considering the historical value of the architectural elements present at the site anchored to the collective memory of the residents, a non-intrusive but decisive approach was selected to bring new uses to the space and to the camp.

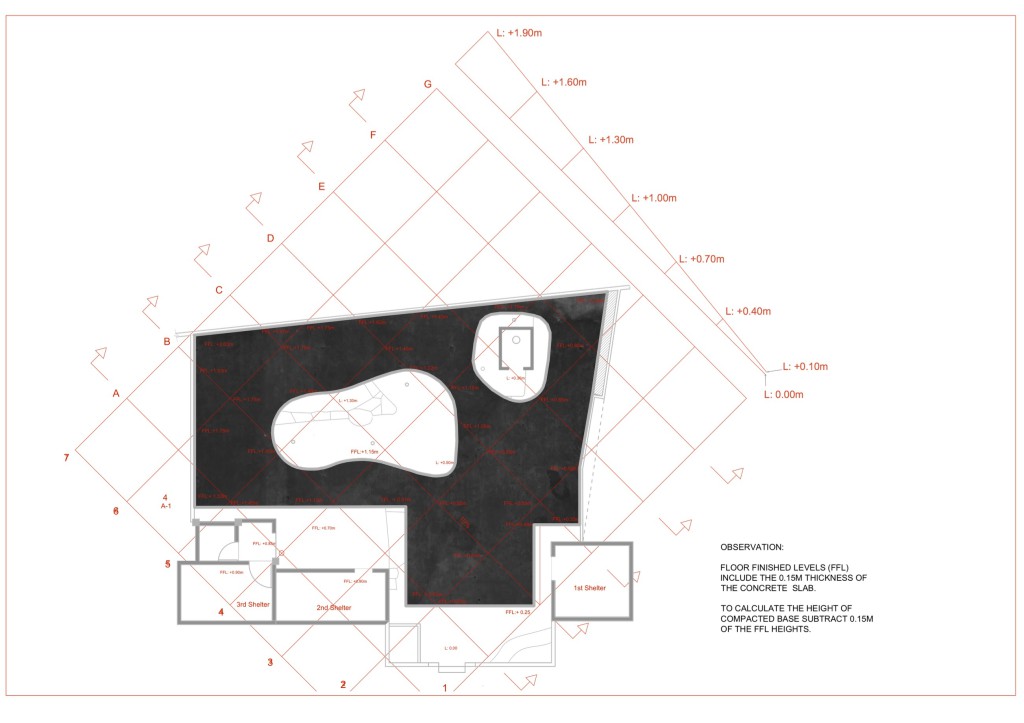

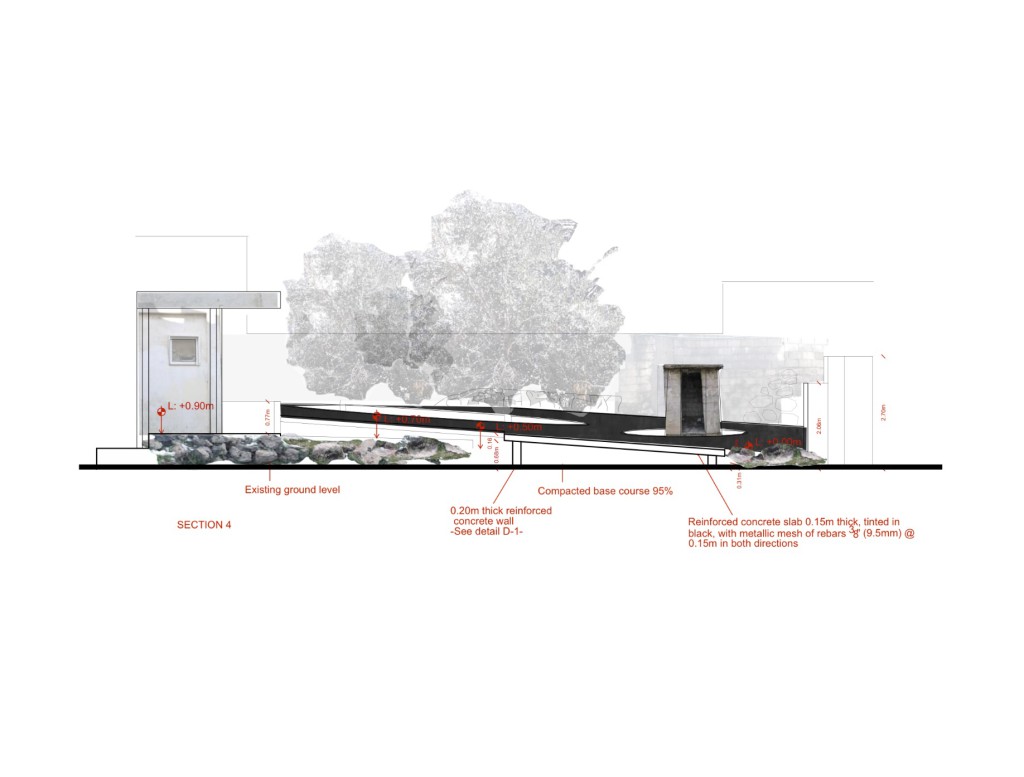

The project was envisioned as a black fifteen centimetre-thick reinforced concrete platform, a sort of theatre stage for events and a neutral frame for the objects present on-site. Similar to temporary structures built for circulation in an archeological site, the black concrete platform was meant to leave the existing shelters as well as the communal latrine, water reservoir and the olive trees intact as a sign of respect for the past in this new beginning.

The platform, built in a way that would appear as “suspended” and “floating” is meant to give the visitors and users the feeling of instability, emphasized by a slight inclination of the platform. The design navigated the tension between the permanency and temporariness of materials and expressed it by architectural form.

The participants of Campus in Camps spent several weeks in dialogue with the neighbour and “owners” of this site and finally an agreement was signed between the popular committee and the family owner of the space to build the project and host activities for all the camp community.

Construction plans began with the excavation for the foundation of the project but after ten days the construction was stopped as the family had now decided to sell the land. The family, the popular committee, and leaders of the camp spent several weeks trying to find a solution. They even offered him another plot but finally the negotiation collapsed after he decided to demolish the shelters.

The plot was left abandoned for months. After, a skeleton for a new house emerged from the site.

This was an extremely frustrating moment, but it also made it even more evident the complexity around “ownership” and the vulnerability of open spaces in the camp, and furthermore it raised the question of how to create a collective awareness on the importance of preserving the camp and its history.

The whole process offered the community a different understanding of the camps: no longer as places without memory but places full of stories that could be told through their urban fabric.

This discovery brought us to the building of a “Concrete Tent”.